History

https://www.odysseytraveller.com/articles/ancient-aboriginal-trade-routes-of-australia/

Since the early 20th century archaeologists could show that Australia was criss-crossed by Aboriginal trade routes. For Isabel McBryde – ‘the mother of Australian archaeology’ – these Aboriginal trade networks were ‘among the world’s most extensive systems of human communication recorded in 'hunter-gatherer'* societies’.

Goods and people travelled vast distances: the Dieri people, east of Lake Eyre, South Australia, visited places at least 800 kilometres apart; while shell from Papua New Guinea reached western New South Wales (Gammage, 149).

Every individual was touched by trade: as archaeologist John Mulvaney has written,

‘it was possible for a man who had bought pituri from the Mulligan River and ochre from Parachilna to own a Cloncurry axe, a Boulia boomerang and wear shell pendants from Carpentaria and Kimberley‘ (Griffiths, 47-48).

Trade had a cultural and social importance, as Mowaljarlai and Malnic (1993) write:

‘The lines are the way the history stories travelled along the trade routes. They are all interconnected. It’s the pattern of the sharing system.’ - [See Map Link Below]

Some goods had a social value that meant they were traded particularly widely. Pearl shells from the Kimberley coast have been believed to have travelled at least 800 kilometres away from their point of origin; with some claiming that they reached as far as the mallee, in western Victoria and eastern South Australia. Some pearl shells were as wide as a small plate, engraved with patterns and worn as a pendant by powerful men.

Stone axes also spread over vast distances. At Calingorady Creek (Moore Creek), near Tamworth, New South Wales, an outcrop of greywacke running along the crest of a saddleback ridge was mined prolifically for over 100 metres. In the 1960s, McBryde used petrological analysis – which had previously been used to show that the bluestone used in building England’s Stonehenge had come from Pembrokeshire, Wales – to examine 517 stone axes that had been scattered across New South Wales. They found that rock from the quarry near Tamworth had been carried as far as Cobar, Bourke, Wilcannia and other parts of western New South Wales – a journey equal to that between Belgium and the south of Spain (Blainey, 191-192).

Ochre was another commodity which was traded widely. Red ochre was particularly important to First Nations peoples across Australia: it was used to adorn the body during ceremonies, decorate wooden implements, and in rock art. The ochre trade is particularly ancient: Mungo Man, the 40, 000 year old ritual burial found in the Willandra Lakes area of Western New South Wales, the traditional meeting place of the Muthi Muthi, Nyiampaar and Barkinji Aboriginal tribes, was covered in over two kilograms of red ochre. The ochre had been brought over 200 kilometres to the burial site (Griffiths, 131).

The first material to be mined in the Flinders Ranges, South Australia, was not copper or gold but red ochre. Ochre from a quarry east of Parachilna township, known as Bookatoo, was celebrated among the Dieri people of central Australia. It was regarded as being of an exceptionally high quality, and held a spiritual importance, believed to be the blood of a sacred emu. The Dieri would send armed bands of 70-80 men 500 kilometres to the south to barter with the traditional owners of the mine, the Adnyamathanha people – even though there were plenty of more accessible ochre mines, such as the Ochre Cliffs near Lyndhurst on the Strzelecki Track.

It is also likely that the Dieri people used their access to the prized ochre to trade for pituri, a psychoactive drug made from the leaves of duboisia hopwoodii, used as both a painkiller and stimulant. The most prized variety of pituri comes from near Bedourie in western Queensland, which was traded north to the Gulf of Carpentaria and south as far as Kurdnatta (Port Augusta South Australia). It is said that pituri provided the one solace for Burke and Wills, slowly dying in remote Central Australia in 1861 (Flood, 202).

The act of trade had a cultural importance; taking on ritual and ceremonial aspects. It shaped the way that landscapes were understood. Particular localities became associated with particular manufactured goods, as different groups made objects with skill that was admired elsewhere. This specialisation was the basis of trade. So, for instance, groups living near Mparntwe (Alice Springs region) were particularly admired for skill in making wooden bowls used for liquids. Specialisation was a source of identity, often expressed through local mythologies (Blainey, 194).

The extensive travel that trade required meant that Aboriginal people had a vast knowledge of the world in which they lived, far beyond their direct locality. They used knowledge of the stars to guide them on long journeys; and had understandings of places that they did not have direct experience of. Early West Australian settler George Moore observed that ‘the natives are all aware that [Australia] is an island’. In 1840, men near Fowler’s Bay, South Australia, correctly assured Edward John Eyre that there was no inland sea; while Sturt recalled that Toonda, his guide in 1844, was able to accurately draw a plan of the Murray-Darling river system.

Aboriginal people studied the world that surrounded them, exchanging long-distance visits to learn of far-away lands and skills. Songs and ceremonies, holding practical knowledge needed for survival and navigation of the land, travelled thousands of kilometres in a short period along what is known as Songlines.

Anthropologists were astounded, for example, when Aboriginal women in Kurdnatta (Port Augusta), South Australia, accurately provided details of places in a song series describing Mparntwe (Alice Springs region), 1200km away. They were able to trace the trading of the ceremony, songs, stories, dances and art back to Mparntwe via the outback South Australian town of Utnadata (Oodnadatta).

This trading of songs can be thought of as a trading of intellectual property to assist travelling. Aboriginal people travelled a lot. They renewed and created relationships and socialised at small ceremonies and huge gatherings. They travelled for seasonal harvests on land, in rivers or at sea, either seeking or avoiding dominant weather events. If you knew the songs, you held knowledge of the land to aid navigation as well as find water and food resources.

Trade also necessitated linguistic dexterity, as Walter Roth, the ‘Aboriginal protector’ of Northern Queensland, recalls:

Picked men may be sent to a distant tribe just for the sake of learning [a dance] … It may thus come to pass, and almost invariably does, that a tribe will learn and sing by rote whole corrobborees [sic] in a language absolutely remote from its own.

Though there was no common language across the continent, there was extensive contact between different language groups. Children frequently had parents who spoke different languages. People spoke up to three or four languages, and some could understand several more; making Aboriginal Australians among the world’s most multilingual people. Such multilingualism is still common today, with people in Arnhem Land frequently speaking English as a third (or thirteenth!) language.

Dialect chains enabled long-distance communication. For example, Group A was able to understand Group B, who understood Group C, but Group A might not have been able to understand Group C (Flood, 173). In Central Queensland and the Western Desert, these chains extended over 3000 kilometres.

THE PANARAMITEE ROCK ART TRADITION: MARKINGS IN THE LAND

The extent of cultural exchange between Aboriginal groups is indicated by the widespread Panaramitee rock art style – also known as ‘track and circle’ – which is found across mainland Australia and Tasmania.

The style was 'discovered' by Bob Edwards, an amateur field photographer on a survey of north-east South Australia with his mentor, Charles Mountford. One of their starting points was the series of engravings found at Panaramitee Station.

Moving from station to station, they found over a thousand similar pieces of art, depicting animal tracks and circles, and less frequently crescents, human footprints, radiating lines, and other nonfigurative designs. These same motifs appeared in a number of sites.

Early European explorers had believed the engravings to be fossil footprints, or the result of algae and lichens eating into rock. But it was clear that they were human markings, formed by pecking with a stone hammer into the rock, which were then covered by ‘desert varnish’, a shiny, rust-coloured accretion that builds up over a long period of time. Mountford believed that the varnish was evidence that the carvings were extremely old, confirmed by his interviews with Aboriginal elders, who claimed that the engravings ‘had always been there.’

As Edwards and Mountford ended their survey, the rains hit, filling rockholes and causing creeks to flow. This stroke of good luck revealed to them another continuity of the engravings: each was next to a waterhole, or other form of supply.

Over the following three years, Edwards collected instances of this style across South Australia and the arid centre of Australia, virtually all associated with water sources and arid camp sites. He had uncovered what archaeologists call a ‘stylistic unit’, the artistic signature of an ancient, widespread cultural tradition. The consistency of the drawings led him to believe that these motifs predated ‘the time when tribal boundaries became rigid and separate cultural entities developed.’

In 1966, as part of a team of researchers led by John Mulvaney, Edwards uncovered tracks and grooves resembling the Panaramitee engravings, at a site west of Katherine, in the Northern Territory. They were able to date the engravings at 5000-7000 years old, the first such dating of rock art in Australian history, proving Edwards’ argument that the style was ancient.

In 1974, the archaeologist Lesley Maynard studied engravings in Laura in Queensland, Mount Cameron West in Tasmania, and Ingaladdi in the Northern Territory, each of which she believed to be part of the Panaramitee style. The Tasmanian find was particularly important, indicating that the style developed before the creation of the Bass Strait by rising seas at the end of the Ice Age.

This led her to develop a chronology of Australian rock art. The first was ancient ‘deep cave art’, produced in the last Ice Age; then the homogenous and widely distributed forms of the Panaramitee, also dating to the Pleistocene (Ice Age); and finally the regionally diverse styles of the Holocene (post-Ice Age), both ‘simple figurative styles’, and ‘complex figurative styles’, including the striking Wandjina of the Kimberley, and the intricate X-ray art found in Arnhem Land and Kakadu.

Maynard’s chronology has since been challenged by other archaeologists, including Andrée Rosenfeld, who has argued for greater cultural difference between North Queensland styles and those found in the ‘red centre’. Others have challenged the antiquity of Panaramitee style, suggesting that many of the tracks do not actually date back to the Pleistocene. Many of the artworks found in the central deserts of Australia are of much more recent origin, indicating a continuation of the style into recent years across a large part of Australia (Griffiths, 174-199).

TRADE IN SOUTH-EAST AUSTRALIA:

The trade of Aboriginal peoples in south-east Australia (southern New South Wales and Victoria) has been extensively studied by Isabel McBryde.

In particular, greenstone axes produced at the Mount William Stone Hatchet Quarry (known as Wil-im-ee Moor-ring), on the outskirts of Melbourne, were revealed by McBryde to have travelled over 1000 kilometres across southern Australia. The quarry today, listed as a National Heritage Place, bears the scars of thousands of years of mining by the traditional owners, the Wurundjeri. Deep pits were dug to reach unweathered stone; and the surface of boulders were heated to break away pieces of rock. The heads were then shaped using a large boulder as an anvil, which were then shaped further by their new owners.

Though the whole tribe had an interest in the place, it was under the special custodianship of one man (in the 19th century, a man named Billibellary), who had inherited this from his father, and traded stone for weapons, rugs and ornaments. In one instance, a visitor exchanged a possum-skin rug for three pieces of the stone (McBryde, 148). It seems to have supported a sedentary population: one settler described thirteen ‘warm and well constructed huts’ near Mount William (Gammage, 300).

Stone from the quarry reached the numerous groups of the Murray River, as far away as Yelta (near Mildura). Early settler Isaac Batey was told in 1862 by an Aboriginal stockman from the Lachlan River, New South Wales, that stone for hatchet heads came ‘from a hill down in the Melbourne country’ (McBryde, 133), while the stone also reached Guichen Bay, near Mount Gambier, South Australia.

In turn, the people of the Murray produced goods from the roots of kumpung river grass. Twine was made by twisting fibre, which was used for fishing line; bags, belts and headbands; for binding axe heads; and for ritual purposes. It was also knotted into nets, used to fish and catch emu, ducks, and small animals. Each group needed around thirty-five kilometres of raw twine to have a set of nets, which meant that twelve kilometres of twine had to be manufactured each year. In total, the process of creating a net took around a year of 35-hour weeks. The work of preparing twine and smaller nets was done primarily by women, while men worked on the larger nets. Much like in pre-industrial England, work was cooperative and social, as people sat around, gossiped, and told stories while producing objects.

Great trading meetings were held on the Murray River. These festivities were often tied to particular food harvests, such as the collection of taarp (lerp), a carbohydrate secreted on eucalypt leaves by plant-eating insects, prized for its sugary taste.

The eel harvest of the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape – a sophisticated aquaculture system that is believed to have supported a sedentary population – was another major festivity, which attracted people from as far away as New South Wales and South Australia to feast on smoked eels caught in the traps. The Brewarrina Fish Traps of northern New South Wales were also host to one of Eastern Australia’s great festivities, with huge numbers of people coming to partake of the harvest, with fish complimented by flour-based breads.

PATTERNS OF EXCHANGE IN ARNHEM LAND:

At the other end of Australia, the trading and exchange patterns of the people of Arnhem Land have also been extensively studied. Thanks to challenging tropical conditions and the fierce resistance of the local Yolngu people, Arnhem Land was never conquered or systematically settled by British colonisation. For the British, its history is a series of failed military, pastoral and mining settlements. As a result, traditional Yolngu life patterns have remained strong to this day.

In the 1930s, the anthropologist Donald Thompson studied the trading patterns of the Yolngu people extensively. Thompson found that every individual in Arnhem Land was a part of a ‘great ceremonial exchange cycle’. A man on the Lower Glyde River, for example, would have received black pounding stones from the east; possum fur, dillybags and spearheads from the south-east; boomerangs, hooked spears and ceremonial belts from the southwest; heavy fighting-clubs from the north-west; and foreign goods (traded by Macassan sailors) from the coastal north-east, calico, blankets, tobacco, knives and glass, much of which he traded away in further exchanges.

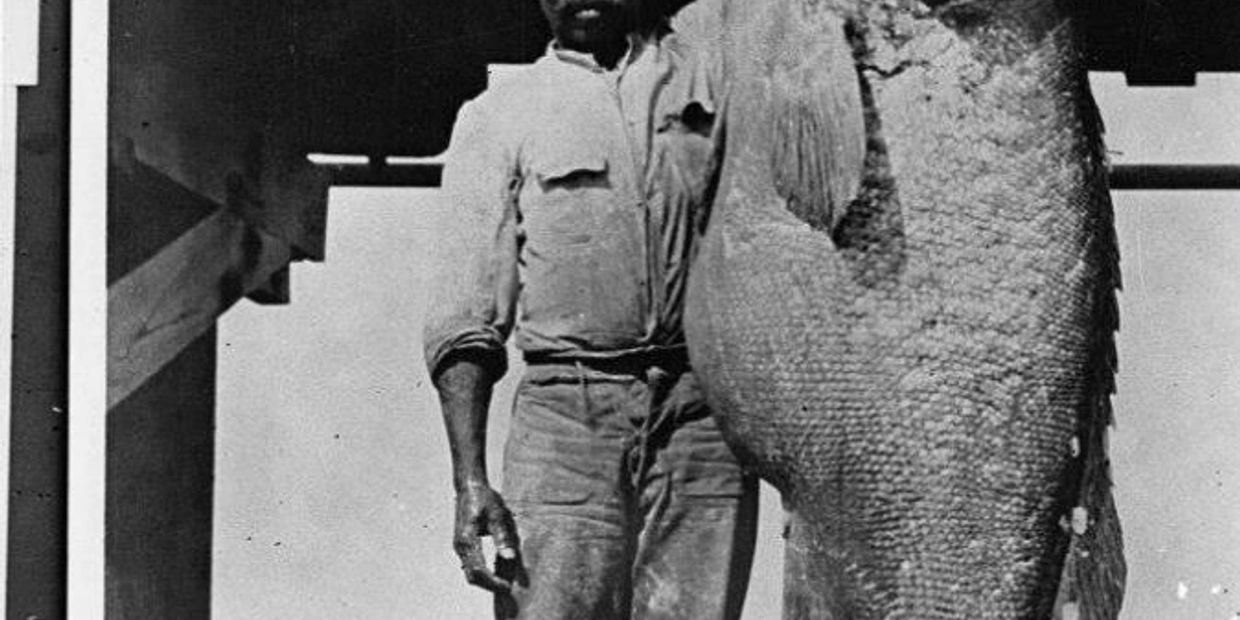

FISHING

This exchange cycle was at the heart of Arnhem Land culture: each individual was under a social obligation to send gifts to partners in remote areas. The act of giving gave esteem, while slowness and a lack of generosity in giving earned disapproval, even social ostracism.

Unlike trade elsewhere in pre-settlement Australia (with the exception of the trade between Cape York, the Torres Strait Islands, and Papua New Guinea), Arnhem Land formed part of a truly international network of exchange. For centuries fishermen and voyagers from Makassar, a city on Indonesia’s Sulawesi island, searched the shores of Arnhem Land in search of trepang, a sea cucumber prized as a delicacy in China.

Anthropologist Campbell Macknight suggested that the trade began between 1650 and 1750, while later scholars such as Darrell Lewis and Anne Clarke have argued that the Macassans started visiting much earlier, around 1000 years ago. The trade only came to an end in 1907, outlawed by the brand-new Australian government.

While on the shores of Arnhem Land, the Macassans grew rice, built stone hearths, and traded with the local Yolngu community, exchanging tobacco, pipes, beads, belts, cloth, iron knives and axeheads and strong dugout canoes, known as lippa-lippa, for the right to fish on Australian waters and employ local labour. They introduced new technologies, such as the dug-out canoe, and inspired a shift in diet to one including more seafood. Macassan words entered the local languages, and some Yolngu people even spent time in the city of Makassar.

The Makassars were integrated into the global trade network, passing goods on to China and using Dutch coins (thanks to Dutch colonisation in Indonesia). The extent of global connection to Arnhem Land is displayed by the mystery of a 12th century African coin found by a serviceman during World War Two.

Macassan goods travelled widely in Australia, even down to the ‘red centre’: botanist Christopher Giles found in a rainmaker’s bag by the Finke River, in central Australia, ‘a curious examples of extremes meeting’, pearl shells obtained from ‘the Malays’ and a boy’s marble from Adelaide.

THE BODY OF AUSTRALIA: A CONNECTED CONTINENT:

Evidence of the trade routes in Aboriginal Australia indicates that Australia was a network of peoples ‘economically integrated’ by the Dreaming. Ngarinyin lawnan David Mowaljarlai, the late elder of the Kimberley, Western Australia, detailed the interconnectedness of Aboriginal people in his map Bandaiyan, Corpus Australis (The Body of Australia) - [See Map Link below].

On his map the whole continent and its islands are joined in a single grid system of social and spiritual connections. The diamonds within the pattern are communities of Aboriginals and the lines connecting them the ancient trade routes and Dreaming pathways that Mowaljarlai calls ‘landstories’. At the nodes connecting the lines is concentrated knowledge – sites of significance or ‘story places’ in which knowledge is embedded. Corpus Australis represents the country as connected through these nodes in the sharing of resources and technology over millennia.

The map of Australia is remapped by Mowaljarlai as a map of the human body, with the line from the Gulf of Caprentariria to the Great Australian Bight the spinal column on which the body is constructed. Cape York and Anhrem Lands constitutes the lungs, Uluru the bellybutton, the Great Australian Bight the public sections, and the southern offshore islands the feet.

For Aboriginal people, society, the environment, and the individual person are not separate from each other. Rather they are united in what the author Mudrooroo describes as “the unity of the people with natural and all living creatures and life forms”. Life and land are intimately connected in a vast network interwoven across vast landscapes.

Many of the most successful exploits of settlers and explorers was thanks to their making use of older Aboriginal trade routes. John McDouall Stuart, the first European to cross the Australian continent, followed an Aboriginal route that led traders from spring to spring in the harsh South Australian outback, linking Cape York and the Kimberley to the southern coast. This route was used in the 1870s to establish the Australian Overland Telegraph Line, connecting Port Augusta to Darwin, with the help of camels and camelmen from the Middle East and Asia.

The route was later used by camel trains led by ‘Afghan’ cameleers to haul goods into central Australia and formed the base of the Great Northern Railway, known as the Ghan, which closed in 1980.

Similarly, the cattle thief and bushman, Harry Reardon, was able to successfully transport 1200 head of stolen cattle from Bowen Downs Station, 130 kilometres north of Longreach, 1000 kilometres south to Hill Hill Station, South Australia, thanks to his communication with Aboriginal people, which allowed him to navigate the desert successfully. The route he established from Lyndhurst to Innamincka was one long traversed by Aboriginal traders, who transported red ochre from the Ochre Cliffs near Lyndhurst north to the Gulf of Carpentaria and south to the Southern Ocean, today known as the Strzelecki Track.

The town of Halls Creek, Western Australia, was an important place of exchange for the traditional owners, the Jaru and Kija people, thanks to its location on the trading routes stretching from the centre of Australia to the Kimberley coast. Even in the cities, many of today’s major landmark have long been ceremonial gathering places for Aboriginal people, including the Melbourne Cricket Ground and King’s Park, Perth.

- Nic Peterson, Odyssey Traveller https://bit.ly/3erMQs6

- - - - - -

REFERENCE MAPS:

Map of trade routes and storylines linking Aboriginal nations across Australia named 'Bandaya', by David Mowaljarlai (1928 - 1997), senior lawman of the Ngarinyin people in the West Kimberley Western Australia: https://bit.ly/3HjAwXh

Map showing the extent of Map showing the extent of Panaramitee style carvings. Image by Ellen Tiley. Image by Ellen Tiley. https://bit.ly/3FCHMxa

Sent from my iPhone

Dampier and Cook

Part of William Dampier’s description of the Aborigines on the north-west coast of Australia. (After the account in his New Voyage round the World 1697)

..."The inhabitants of this country are the miserablest people in the world. The Hodmadods of Monomatapa, though a nasty people, yet for wealth are gentlemen to these; who have no houses and skin garments, sheep, poultry, and fruits of the earth, ostrich eggs, etc., as the Hodmadods have; and setting aside their human shape, they differ but little from brutes. they are tall, straight-bodied and thin, with small, long limbs. they have great heads, round foreheads, and great brows. Their eye-lids are always half closed, to keep the flies out of their eyes, they being so troublesome here that no fanning will keep them from coming to one’s face… so that, from their infancy, being thus annoyed with these insects, they do never open their eyes as other people do; and therefore they cannot see far, unless they hold up their heads as if they were looking at somewhat over them.

They have great bottle-noses, pretty full lips and wide mouths, the two fore-teeth of their upper jaw are wanting in all of them, men and women, old and young: neither have they any beards.

They are long-visaged, and of a very unpleasing aspect, having no one graceful feature in their faces. Their hair is black, short, and curled, like that of the negroes; and not long and lank … the colour of their skins, both of their faces and the rest of their body, is coal black, like that of the negroes of guinea.

They have no sort of clothes, but the piece of the rind of a tree ty’d lyke a girdle about their waists, and a handful of long grass, or three or four small green boughs, full of leaves, thrust under their girdle to cover their nakedness.

They have no houses, but lye in the open air without any covering the earth being their bed and the heaven their canopy. Whether they cohabit one to one women, or promiscuously. I know not. but they do live in companies, twenty or thirty men, women and children together. their only food is a small sort of fish, which they get my making wares of stone across the coves or branches of the sea; every tide bringing in the little fish, and there leaving them a prey to these people, who constantly attend there to search at low water.

I did not perceive that they did worship anything. these poor creatures have a sort of weapon to defend their ware or fight with their enemies, if they have any that will interfere with their poor fishery. They did endeavour with their weapons to frighten us who, lying ashore, deterr’d them from one of their fishing places. some of them had wooden swords, others had a sort of lances. the sword is a piece of wood shaped somewhat like a cutclass. the lance is a long strait pole, sharp at one end, and hardened afterwards by heat. I saw no iron, nor any other sort of metal; therefore it is probable they use stone hatchet.

How they get their fire I know not but probably, as Indians do, out of wood.”"

Yow!!, keep away from there…….

After Dampier it was some time before other navigators had much contact with Aborigines.

Dampier and Cook

The Breaking Down of Aboriginal Society continued

Discovery

.... After examining Australia’s eastern coast in 1770, Cook wrote more favourably about the Aboriginal inhabitants:

They may appear to some to be the most wretched people upon Earth, but in reality they are far more happier than we Europeans; being wholly unacquainted not only with the superfluous but the necessary Conveniences so much sought after in Europe, they are happy in not knowing the use of them … the Earth and sea of their own accord furnished them with all things necessary for life …

Aborigines in early Sydney and other districts could see little point in many European practices. They did not need to cultivate the soil or keep domesticated animals, since the natural environment provided for their wants. Similarly they saw little need for European learning and religion – they had their own skills and their own explanations of the world around them. In fact Aborigines often proved the better teachers... they showed white settlers the trees that provided the best timbers for various purposes and how to cut and treat bark for hut making; they showed how to obtain bark fibre, valuable for rope, and other skills.

The whites claimed that physical clashes occurred because Aborigines were naturally wicked and loved fighting. The claim was not accurate. Aborigines in their own society were a peaceful people. Fighting was usually on a limited scale, often stopping when the first blood was drawn. there was nothing like the wars known among European people for territory, nor did Aborigines form large-scale combinations for fighting.

And Aborigines could scarcely have been impressed by what they saw among the new arrivals, for convict society offered daily examples of harshness and ill-treatment.

White people also claimed that Aborigines had no idea of land ownership, therefore white settlers could not be dispossessing them. why, they asked, did Aborigines resent the new arrivals so much? Part of the answer was already apparent to Governor King, who became governor of New South Wales in 1800.

He realized that loss of land was a major reason for trouble, although settlers continued to claim Aborigines had no land of their own. Whites would not learn from the example of Bennelong, the Aborigine they knew best, who repeatedly declared that the island of Me-mul (Goat Island), near Sydney Cove, was his own and his family’s home. Like other Aborigines Bennelong was deeply attached to his land. to be forced from their group land meant that Aborigines lost their spiritual homes as well as their source of food. In occupying Aboriginal land, whites drove off game, destroyed vegetation, fouled waterholes and showed no respect for sacred places.

Aborigines and White Settlers

When the first European settlers arrived in 1788 the Aborigines were the sole occupants of Australia. A hundred years later Aborigines no longer held much of the continent, and many Aboriginal groups were struggling for survival. Almost everywhere white settlement had proved overpowering.

There had been no peaceful adjustment between whites and Aborigines, and the frontier between them had many times been marked in blood. Even where white settlement was sparse, traditional Aboriginal society was often strongly influenced by the presence of the new arrivals.

White people, claiming they had greater natural abilities and a higher standard of civilisation, soon justified what was happening. When they later looked backwards on their short time in Australia, they began to revere the achievements of pioneering whites. The achievements of the Aboriginal people, and the story of what had happened between whites and Aborigines, were ignored or quickly passed over.

The European Explorers

Before 1788 the Macassan seamen were not the only visitors to Australia’s shores. European explorers, especially the Dutch, began to make contact with Australia’s coasts in the seventeenth century. The Dutch, making their way from their Indonesian trading posts, were probably the first white people Aborigines had seen. Contacts between them were very limited, for the Dutch made only fleeting visits to the coastline and had been instructed to be careful in any contacts with people found there – possibilities of trade must not be spoiled. The Dutch went back however to report that there was no chance of trade, for the land seemed miserable and full of flies. the Aborigines, unimpressed with the trinkets shown to them, resented the visitors, who had attempted to kidnap some of them. Fear, hostility and occasional bloodshed marked contact between the two sides.

In 1688 and 1699 the buccaneering Englishman William Dampier visited Australia’s north-west coast. He gave Europeans a more detailed version of Aboriginal life. Without other versions to compare them with, Dampier’s views became widely known and accepted. His lack of understanding led him to a disgust of Aboriginal life, influencing others to a similar conclusion.

His description helped to establish the typical beliefs and attitudes – the stereotypes – that future white people were to hold about Aboriginal Australians

For Aborigines … land is a spiritual thing...

A modern writer, Professor Colin Tatz, has shown the nature of what was happening:

For Aborigines … land is a spiritual thing, a phenomenon from which culture and religion derive, it is not sellable or buyable. Land is not private property … Land was and is endowed with a magical quality, involving a relationship to the sun and the water and the earth and the animals all put together – for the collective use of all. The notion of a fence to separate portions of the land was unknown to them for fences defaced the land.

They could not, and some still cannot, understand the concept of making land into private property and giving its ‘owners’ the right to bar everyone else … And so bloody conflict and massacre developed … because whites ‘took’ what Aborigines did not comprehend could be ‘taken’.As white settlement spread after 1800, clashes continued. Officials in Britain and New South Wales thought the matter was simple. the British Crown was held to own the land.

People of both races inhabiting the land were claimed to be British subjects. Aborigines were neither consulted nor given a choice. They were actually declared to be under the protection of the law, but this proved little. In fact whites were those who clamoured for protection and who received it most. With the wool trade becoming more prosperous, settlers then began settling on new grazing land after the Blue Mountains were crossed.

In more distant areas official protection of either race was more difficult and often not attempted...violence – ‘guerilla warfare’ – extended again along the frontier of settlement. guns were at the ready, or were used, on many pastoral properties. Aborigines, too, took to arms, using spears against settlers and stock. Inevitably, clashes ended in the taking of Aboriginal land and the subjection of the people.

The nature of relations between Aborigines and Europeans varied in different districts and was not always violent. European diseases were often the most destructive agent in the decline of Aboriginal groups.

Surviving Aborigines began to live in towns as well as country areas. European missionaries sought to break down Aboriginal beliefs and convert Aborigines to Christianity, but they also tried to provide some relief to suffering Aborigines. Yet by the 1830s relationships between Europeans and Aborigines were at a critical stage.

European settlers had seized great stretches of country in New South Wales. some pitched battles and other incidents were of major significance. In northern New South Wales in 1838 a group of station-hands killed twenty-eight bound Aborigines in what became known as the Myall Creek Massacre.

In this case, unlike many others, the seven station-hands held to be responsible were convicted and hanged for their crime, despite white sympathy for them. Many whites seemed to share the view of a writer a little earlier “Speaking of them collectively, it must be confessed I entertain very little more respect for the aborigines of New Holland, than for the ourang-outang … ‘they would have shared his further opinion:” ‘They would have shared his further opinion: ‘We have taken possession of their country, and are determined to keep it …’

The Other Colonies

In Van Diemen’s Land the position was even worse. In 1804, soon after white settlement began, some ‘innocent and well disposed’ Aborigines were murdered at Risdon Cove, starting a chain reaction of unpleasant incidents.

Lawless sealers and convicts, in murdering Aborigines and kidnapping Aboriginal women, provoked Aborigines to hatred and a desire for revenge. The settlers wanted to solve the Aboriginal question decisively; some simply wanted to exterminate all Aborigines on the island. they looked to the governor, Lieut.-Colonel Arthur, to take strong action. After several futile measures, Arthur tried to outlaw Aborigines from the settled districts. Soon he declared martial law and began in 1830 an amazing military operation, in which five thousand whites attempted to drive the remaining Aborigines into the Tasman Peninsula.

This so-called ‘Black War’, said to be extremely costly, failed dismally – only two Aborigines were captured. It was left to George Robinson, a bricklayer of simple faith, to attempt a government policy of conciliation.

Making contact with surviving groups, he persuaded Aborigines to make their home on flinders Island. though this provided some physical safety, Aborigines now lacked the spiritual comfort of their own lands. Urged to accept strange European customs and learning, Tasmania’s Aborigines continued to decline in numbers.

By 1850 few survived.In Western Australia, settled in the 1820s, the early aims of protecting, Aborigines and offering them the benefits of European learning and religion were, as elsewhere, soon outweighed by other concerns. governor Stirling allowed whites to take strong measures against Aborigines said to be causing trouble. Stirling personally took part in the ‘Battle of Pinjarra’ to punish Aborigines of the Murray River district south of Perth. Once again the Aborigines faced strong pressure from whites determined to occupy the land and use arms if they chose.

At Port Phillip Bay in 1835 an initial attempt was made at land negotiations. John Batman, an ambitious pastoralist from Van Diemen’s Land was anxious to secure good grazing land near the Yarra for himself and his partners. Unable to win official approval to settle there, Batman simply bargained with local Aborigines for a large tract of land. the New South Wales governor declared this private treaty illegal, and although settlement at Port Phillip expanded quickly and profitably for other whites, Batman obtained no benefit from his curious deal. Nor did Aborigines, who soon found their traditional life decaying and their numbers declining. This was despite the appointment of official protectors of Aborigines, the founding of mission stations and schools, and an attempt to form a ‘Native Police’ force which recruited Aborigines themselves for police work.Great hopes were held that South Australia, settled in 1836, would be free of the racial troubles elsewhere.

In Britain officials influenced by the humanitarian movement of the time were anxious to give South Australia’s Aborigines much greater protection and the blessings of British ways and the Christian religion. they believed South Australia could be a model colony in this respect. Although a protector of Aborigines was appointed and although a good deal of humanitarian talk about kindly treatment took place, efforts and results were feeble.

The Kaurna people around Adelaide was soon shattered as a unit. Aboriginal groups surviving longer felt limited benefit from occasional educational, missionary and welfare attempts. Far from being a model colony in its relations with Aborigines, South Australia resembled the other colonies in the rapid occupation of Aboriginal lands, the physical violence between the races, and the settlers’ ignorance of the nature of Aboriginal society.

And once again the original idea of giving protection to Aborigines soon gave way to settlers’ demands for protection from Aborigines, especially after clashes involving overlanders bringing stock to South Australia.In northern Australia Aborigines and whites engaged in an often violent struggle in the Moreton Bay district (part of the future colony of Queensland).

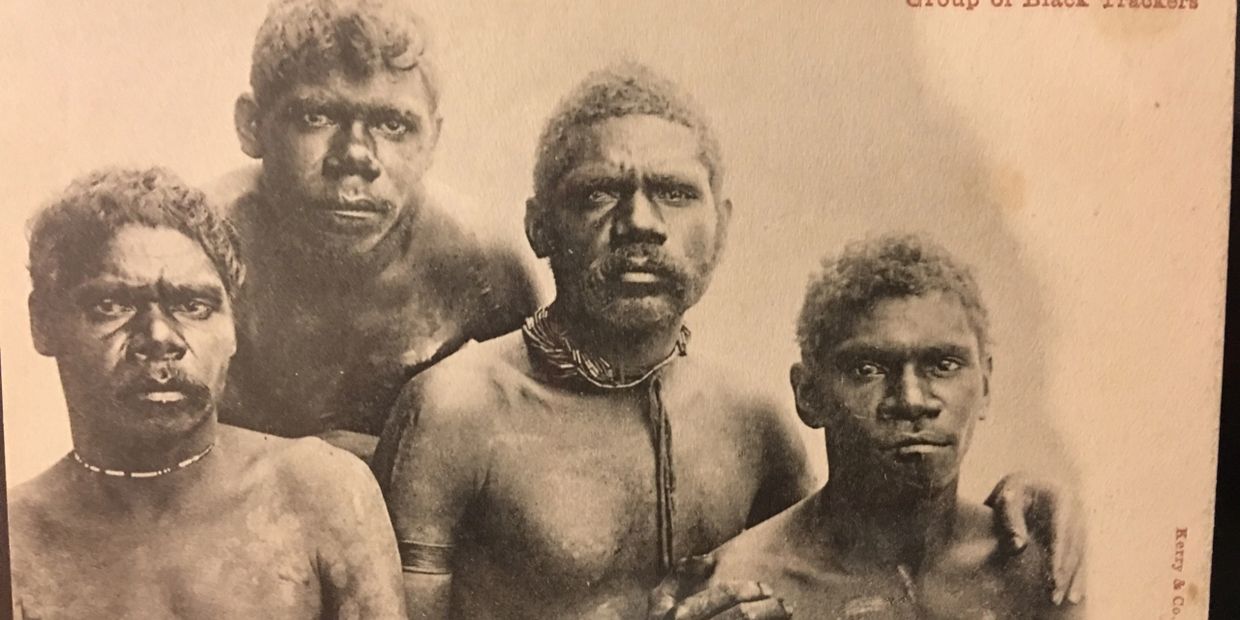

White settlers often resorted to poisoned food and guns along the very troubled frontier. As settlement advanced, the Native Police force – used before in Victoria and New South Wales – became prominent. These mounted Aboriginal troopers, enlisted from remote districts to use their skills of bushcraft against their own race, were trained to enforce peace, ruthlessly as pastoral holdings were developed. For whit3es, the possession of potentially valuable grazing land in the Darling Downs and other areas was at stake; for local Aborigines, this was traditional land and the lifeblood of their existence.

Only on stations where their labour was valued were Aborigines welcome; elsewhere they were likely to be attacked indiscriminately. In the Northern Territory things were no better. From the time of John McDouall Stuart’s explorations, the Northern Territory was a scene of racial conflict, a conflict marked by mistrust and violence in which guns, spears and staghounds often featured. Administrators made only feeble efforts to calm the situation. Matters were left to the settlers themselves or entrusted to police leading punitive expedition and forces of Native Police. Cattle spearing would often be the reason given for such an expedition, frequently leading to loss of Aboriginal lives.

The Impact of Settlement

Aborigines And White Settlers

Such actions hastened the decline of Aboriginal groups during the nineteenth century, though the decline went on even where there was friendship and trust on both sides. The decline came despite the setting up of government ration-stations to distribute flour and blankets to needy aborigines, and despite the work of missionary establishments and official protectors of Aborigines.

It came, too, despite the often spirited resistance of Aboriginal people to the seizure of their land and the attacks on their culture. the land question lay at the heart of the decline of traditional Aboriginal society. The declared attitude of the British and colonial governments remained clear: the land, ‘waste and uncultivated’, belonged to the whites, even if they had not yet occupied parts of it. Even where some land reserves were set aside for Aborigines, the colonial governments claimed actual ownership of the reserves and white pastoralists could often graze their stock there. Only a few whites admitted that Aborigines were being dispossessed of their land.

The Aboriginal people regarded white settlement as an unjustified intrusion on their lands. Sheep and cattle began to eat out the native grasses and drive off the game which provided essential meat food. The situation was made worse by the white pastoralists’ determination to control the existing waterholes, soon fouled by stock. There was an increasing upset in the balance between Aboriginal population numbers and the available food supply. the white intruders showed no desire to compensate, and did not acknowledge the food-sharing practices found among the Aboriginal people themselves.

The situation, of course, was not simply an economic one, since whites and their stock were occupying sacred Aboriginal places, such as the totemic sites to which Aborigines were reverently attached. It was little wonder that Aborigines began their own campaign of spirited resistance on the frontier of settlement. They speared stock which were on their haunting-grounds and which they thus believed they were entitled to hunt. In many areas a bitter racial conflict began, in which Aborigines were at a disadvantage in arms, especially when whites could make greater use of rifles in the latter part of the nineteenth century. The first interest of white governments came to be to provide protection from the Aborigines, rather than of them.

Police action, punitive raids and began enforcement were some of the methods used. It is no exaggeration to conclude that actual warfare thus took place over a long period in Australia.

One Law for All

In legal proceedings Aborigines were at a considerable disadvantage. Because Aborigines were regarded as incapable of understanding the oath in European courts, their evidence was not accepted. When this situation was later corrected, Aborigines were still greatly disadvantaged. No Aborigine appeared as prosecutor, juror or judge. Court procedures and the legal code were European, and bewildering to Aborigines.

Aborigines also became victims of bias and prejudice in courts, which were anxious to uphold white dominance and did not acknowledge Aboriginal title to the land. the punishment system made matters for worse – its basis w3as not understood and it left Aborigines confused and very fearful.The Europeans’ failure to consider Aboriginal law and customs was part of the pattern of white supremacy. this made no allowance for Aboriginal practices. In traditional society, of course, Aborigines were bound by strict obligations and codes of conduct, which whites simply refused to recognise.

Aborigines settled disputes by different means, involving actual or ceremonial punishments and not detention. the idea was to restore normal group life as quickly as possible. Whites were unwilling or unable to understand the Aboriginal system. They failed to observe obligations which Aborigines thought should apply to whites as well as themselves. This caused much Aboriginal resentment – especially the practice of whites trespassing on Aboriginal land and the troubles arising from the whites’ desire for relationships with Aboriginal women.

Translation of Aboriginal languages caused problems in court, and Aboriginal customs and law were not taken into account. The position was made worse by the Aboriginal tendency to look for, and give, the answer required by the prosecution.

Colonisation in Qld

By 1901 Aborigines had lost control over their land in all except the remote parts of the continent. They were not given the chance to determine their own future. their culture was not respected. Aboriginal languages were dying out with the people. Few whites took, the trouble to learn anything about Aboriginal life; many whites regarded Aborigines as oddities or nuisances. Along the frontier the view was still usually the same – ‘Bullocks and blacks won’t mix’.

It was hoped that the establishment of the new federal government, in 1901, would lead to a better deal for Aborigines. There were even suggestions that the new government, and not the separate states, should have responsibility for Aboriginal affairs. But things changed little. It was decided, for example, that Aborigines should not be counted in the feral census. thus the original owners of the land were officially not counted or regarded as Australians. the federal government had no new views on Aboriginal affairs, which remained the responsibility of the individual states. State laws reflected the desire to restrict and segregate Aborigines.

A Queensland Act in 1897 set the pattern. It gave the official protectors of Aborigines wide powers to control the lives of the Aboriginal and part-Aboriginal people. It provided for reserves on which Aborigines should live and supervised their movements and employment by whites. Western Australia and South Australia adopted similar legislation, so that Aborigines who no longer lived in their traditional societies often had to live on reserves under government administration.

In effect they had to live as inmates of institutions.The basis, then, of the protection policy was restriction of the Aboriginal people and their rights. As before, there was no attempt to consider what Aborigines themselves might want. Once again whites assumed that the best policy for Aborigines was to adopt white ways. If Aborigines did not follow that path, then it was said they were lacking in ability. there was always the feeling that the Aborigines, not the whites, were responsible for any failure.

Further Trouble in the North

Along the frontier of settlement in the early twentieth century, relations between whites and Aborigines continued to reveal conflict and inhumanity. In outlying areas of the Northern Territory and Western Australia some settlers and bushmen were accustomed to shoot Aborigines on sight or turn their dogs loose at sundown.

Several of the worst incidents were described by Dr. W.E. Roth, who was asked to make a report to the Western Australian government in 1905. He revealed ‘a most brutal and outrageous state of affairs’ in the northern part of the state: there was police corruption in administering Aboriginal ration allowances; the chaining together (by the neck) of arrested Aborigines and Aboriginal witnesses and prisoners, forced labour for Aboriginal children, and heavy sentences for children and adults convicted of killing cattle; discrimination in court proceedings; and a shortage of food.

The Breakdown of Aboriginal Society

As white colonists seized Aboriginal land – land with its spiritual as well as economic importance – there began the assault on traditional Aboriginal society. Beliefs, social customs and morale were weakened as Aboriginal numbers declined. No longer did the social system firmly support Aboriginal groups, ritual duties were no longer performed with the old vigour. The spiritual basis of Aboriginal life was undermined. The whites’ desire to educate and convert Aborigines hastened the breakdown of Aboriginal society. Whites usually described that society as primitive. Aboriginal beliefs and customs were ridiculed, as attempts were made to replace them with European culture. this culture puzzled rather than satisfied Aborigines, to whom it had little relevance. Aborigines found adjustment difficult.

Their own world was one in which tradition was highly important – unlike whites, they placed no emphasis on change. In turn Aborigines were criticised for their apparent unwillingness to live according to ‘civilised’ ways. Meanwhile Aboriginal social life continued to decline. white missionaries, by discouraging initiation ceremonies, hindered younger Aborigines from being accepted as full participants in traditional life. whites encouraged Aboriginal marriages which cut across traditional kinship rules. Other patterns of behaviour, so important in regulating Aboriginal social life, decayed.White settlers usually concentrated on the material problems of colonial life. In the clash for land, especially in remote parts, the settlers’ fear of Aborigines was noticeable.

With their control of the land gone, Aborigines drifted to the edge of towns, pastoral stations and mission stations, attracted by European material items and by food, drink, and tobacco. Hand-outs of ration food and clothing were periodically made, emphasising the unfortunate and dependent state to which Aborigines had been reduced. The availability of alcohol and tobacco began to take a severe toll of Aboriginal health.

Disease

Disease played a vital role in the breakdown of traditional Aboriginal societies. In fact introduced diseases have often been suggested as the major cause of the disappearance of many Aboriginal groups, with a much greater impact than physical violence or any other factor. Before the Macassan visits and the arrival of Europeans, Aborigines had been relatively free from diseases, their chief trouble coming from eye and skin complaints.

The marsupials they hunted did not transmit their diseases to humans. but after the coming of other peoples and their stock, Aborigines began to suffer badly from the new diseases, to which they had no natural resistance. Smallpox, tuberculosis, venereal diseases and leprosy had disastrous effects, while milder diseases such as influenza, measles, whooping-cough and the common cold could be just as deadly to a people with no previous contact with them. Several descriptions stated that in some areas most, or all, of the children died from disease.

Diseases in fact often drastically reduced a local Aboriginal population even before the full pressure of white settlement was felt there. Smallpox destroyed the majority of Aborigines close to Sydney within three years of white settlement in 1788. the disease spread down the Murray to south Australia, shattering she health and numbers of Aborigines as it went.

The ‘smallpox song’ that Aborigines sang was powerless to stop the deadly disease. the death of the traditional Aboriginal ‘doctors’ and the destruction of medicinal herbs by introduced stock removed the traditional Aboriginal sources of relief from illnesses. by 1850 the results of disease were already being felt in the settled areas of southern Australia, where whites were noticing the decline in the Aboriginal population.

Disease robbed Aboriginal people of their spirit and ability to survive. By reducing numbers it broke down the strength of the kinship system and the links between the generations. The birth rate was lowered. Surviving groups were left unable to carry on in the former manner as strong social units. The impact of disease on the social structure of Aboriginal groups and on total numbers was profound.

‘Soothing the Dying Pillow’

As the rapid decline in Aboriginal population took place, few whites tried to suggest reasons. One who did so in 1886 described the grim process and some of its causes: Experience shows that a populous town will kill out the tribes which live near enough to visit it daily in from two to ten years … in more sparsely-settled country the process is somewhat different and more gradual, but it leads to the same end. In the bush many tribes have disappeared, and the rest are disappearing. Towns destroy by drunkenness and debauchery; in the country, from fifteen to five-and-twenty per cent fall by the rifle; the tribe then submits, and diseases of European origin complete the process of extermination.This description showed a general pattern. the process varied in intensity according to districts, and was slowed by the efforts of a few determined showed a general pattern. the process varied in intensity according to districts, and was slowed by the efforts of a few determined whites to help Aborigines.

Not all the Aboriginal groups died out. but long before 1900 most whites thought it was only a matter of time before the Aboriginal people ceased to exist. This apparent dying-out of the whole race helped to end earlier ideas – held mostly by whites in towns – about Aboriginal assimilation into the white community. Instead of different approach was suggested. Its goal was to make the passing of the Aborigines as peaceful as possible. the approach was termed ‘soothing the dying pillow’. To those who cared, the policy seemed a worthy one, though it was also a policy of despair.

As early as 1868, when more than three-quarters of Victoria’s Aborigines had already died out, a Melbourne editor summed up the policy:Let us make their passage to the grave as comfortable as possible – let us do our best to civilize them and convert them to Christianity; but let us not flatter ourselves that, up to the present at any rate, we have succeeded. something may be done with the half-castes, but the case of the full-blooded aboriginal is, we fear, hopeless.Whites tended to make a fuss of the last Aboriginal members of a group, just as they did of those they described as ‘king’ or ‘queen’ of a particular group. In practice, however, few whites, or their governments, did much towards Aboriginal welfare.

Mission stations and government reserves became the enforced homes of many surviving Aborigines, where they were supplied with medicine, shelter, a minimum of food, and the customary blankets. some schooling and elementary training in practical skills could also be provided. governments favoured this policy of segregation, declaring that it would enable Aborigines to avoid contact with the worst of the whites. Yet by encouraging the isolation of Aborigines this policy also enabled white society to avoid Aborigines and the ‘problem’ of Aboriginal welfare. the idea of ‘soothing the dying pillow’ was easy to accept, for it helped to satisfy the few whites who were concerned about the Aborigines’ position. It also left other whites free to pursue their own tasks on the land taken from Aborigines.This Brilliant article by Jane Resture

Dark History 4

The Protection Policies

Whites in the north did not hide their fierce determination to seize and hold the land. this brought them into opposition with some city-dwellers, who questioned not the northerners’ right to the land but the means used to obtain it. “Arguments over the issue sometimes flared in the press. the northerners’ feelings were clear, as shown in a poem, written by one of their supporters:

The civic merchant, snugly housed and fed,

Who sleeps each night on soft and guarded bed,

Who never leaves the city’s beaten tracks.

May well believe in kindness to the blacks.

But he can never know, nor hardly guess,

The dangers of the pathless wilderness;

The rage and frenzy in the squatter’s brain

When the speared bullocks dot the spreading plain;

The lust for vengeance in the stockman’s heart

Who sees his horse lie slain by savage dart;

The nervous thrill the lonely traveller feels feels

When round his camp the prowling savage steals;

Nor that fierce hate with which the soul is filled

When man must daughter or himself be killed.

Ah! who shall judge? Not you, my city friend,

Whose life is free from all that can offend;

Who pass your days in comfort, ease, and peace.

Guarded by metropolitan police.

Ah! who shall judge the bushman’s hasty crime

Both justified by circumstance and clime.

Could you, my friend, ‘neath such assaults be still,

And never feel that wild desire to kill?

Steps in your own defence would you not take

When law is absent then your own laws make.

From 1911, when it took over the administration of the Northern Territory from South Australia, the Commonwealth became more involved in Aboriginal affairs. Its policy of protection resembled the policy found in several of the states. Every aspect of Aboriginal life was carefully regulated.

The Aborigines freedom of movement was greatly restricted. For many Aborigines, life became centred on institutions established under government control, where the opportunity to make personal decisions and live in simple dignity was slight. Special conditions governed their employment, while their personal property remained under the control of the government’s chief protector of Aborigines. The protector, not the children’s parents, was the legal guardian of the children.

Yet the Commonwealth was no more able than the states to improve Aboriginal affairs. The Northern Territory remained prone to racial disturbances, which police solved as they saw fit. In places such as Arnhem Land it was possible for Aborigines to lead a better life, in more traditional manner.... but around white settlements and stations Aborigines camped in poverty, valued only when their labour was essential in the pastoral industry.

The commonwealth seemed to forget they existed, until their condition came to public notice late in the 1920s. At that time drought threatened natural food supplies, bringing concern in southern cities about the Aborigines’ plight.

Site Content

Coniston Massacre

About another matter – the ‘Coniston Massacre’ – there were louder complaints.

Following the death in 1928 of a white prospector at Coniston Station in Central Australia, a police expedition set out to find the culprits. In a series of raids police took heavy toll of Aboriginal lives. The reaction from city people interested in Aboriginal welfare was hostile, and not softened by an official report justifying the raids and the police shooting of many Aborigines. Reports of killings elsewhere, such as in the Kimberleys, and of the miserable conditions which many Aborigines were forced to endure, aroused further concern.

Such troubles revived the arguments between whites in towns and those on the edge of settlement about policies towards Aborigines. Like others earlier, there were settlers who still thought and spoke of Aborigines as a kind of animal, describing them as ‘wild’ or ‘tame’. Many whites still took refuge in the belief that the Aboriginal race was dying out, despite evidence to the contrary. ‘even as late as 1938 Daisy Bates, the well-known worker for the Aborigines on the Nullarbor, published her book under the title of the Passing of the Aborigines.

Malnutrition

Malnutrition and disease continued to play havoc with Aboriginal health as the twentieth century wore on. A white doctor, well informed about the Aboriginal situation, even claimed later that malnutrition was the greatest damage inflicted by the whites and the one least acknowledged with regret. Government and station rations were often inadequate. flour, sugar and tea were the basic rations, following the pattern laid down in the previous century, when governments saw feeding-stations as a means of preventing Aboriginal hunger and thus possibly of preventing the spearing of stock. The absence of protein foods affected Aboriginal health and contributed to high infant mortality. Damp clothing and poor housing brought further suffering. Disease, especially tuberculosis, remained widespread and often fatal.

This wonderful article is by Dr. Jane Resture.

To the invaders the Aborigines seemed part of a strange land with distinctive fauna.

Aborigines were often described as wild while the term savages survived from early days.

Then, after the clash between the races, came the decline of Aboriginal traditional life.

Death of Cook

On February 14, Valentines Day, 1779 Captain James Cook of the British Royal Navy was killed by natives in Kealakekua Bay, on the Big Island of Hawaii.

Cook sailed across the world bringing disaster to native peoples of the Pacific. To his credit he was conflicted about doing this - but it was his duty to serve the Crown...

When he was killed, Cook was trying to kidnap the Hawaiian Aliʻi (tribal chief) Kalaniʻōpuʻu in response to an unknown person stealing a small boat. In the process, he had threatened to open fire on the islanders.

At this point, threatened with murder and the kidnapping of one of their tribal leaders, the Hawaiian islanders attacked him and he died from a knife to the chest.....

- School Workshops

- Ochre Info

- Ochre Here

- More Ochre Info

- Even More Ochre Info

- Ochre Colours Available

- Kangaroo Skins

- Wallaby Skins

- Possum Skins

- Aboriginal Colour in Book

- Free Aboriginal Clipart

- Deadly Dance Costumes

- History

- Gallery

- Aboriginal Shelter Humpy

- Hands on School Workshop

- Aboriginal Workshop

- Quandong Seeds for Crafts

- Beeswax

- Didgeridoos

- Fire Sticks

- Stone Axe

- SDS

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.